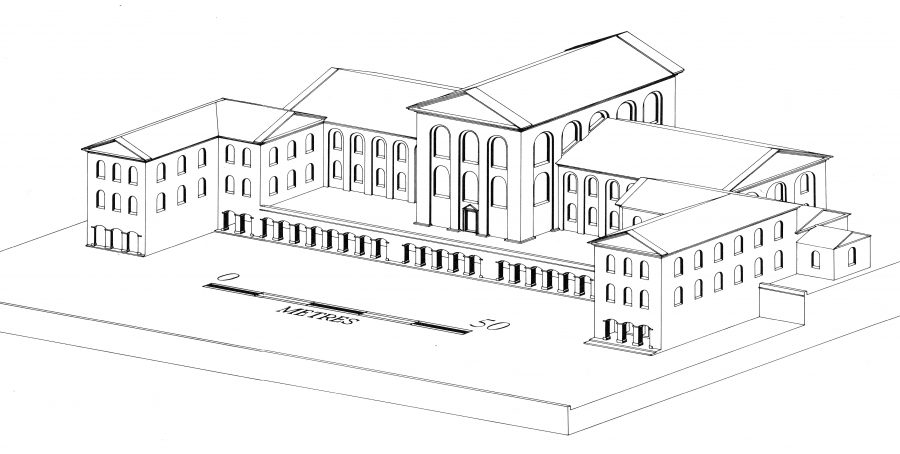

Visualisation of the Castor Praetorium – Mackreth

What is the Castor Praetorium?

The Praetorium was a monumental Roman building which stood proudly on high ground on the northern edge of the Nene valley – on a site since occupied by the parish church of Castor.

It had commanding views to the south across the industrial suburbs of Normangate Field and onwards to the Roman town of Durobrivae in the distance. It was located close to two major Roman roads – Ermine Street and King Street.

It was built around 250AD and was on a grand scale. The structure was raised up on two great terraces. The building(s) covered an area of 290m by 130m and had at least 11 rooms with tessellated floors and mosaics, two bath-houses and several hypocausts.

The term Praetorium was used by Edmund Artis in the 19th century. This suggests some public administrative function but the building could also be seen as a luxury residence or Palace.

Castor Praetorium – Evidence & Finds

A wealth of Roman finds in the Castor area had intrigued early antiquarians. Such was their spread that some believed they formed part of the Roman town of Durobrivae.

William Camden, 1612

‘The Avon or Nen river, running under a beautiful bridge at Walmesford (Wansford), passes by Durobrivae, a very ancient city, called in Saxon Dormancaster…. the little village of Castor, which stands one mile from the river, seems to have been part of it, by the inlaid chequered pavements found there.’

John Morton, 1712

‘… the Castle or principal Fort or whatever, the Place of Residence of the chief Officer was upon the Hill where the church at present stands’.

William Stukeley, 1724

‘Below the churchyard the ground is full of foundations and mosaics. I saw a bit of a pavement in the cellar of the alehouse…’

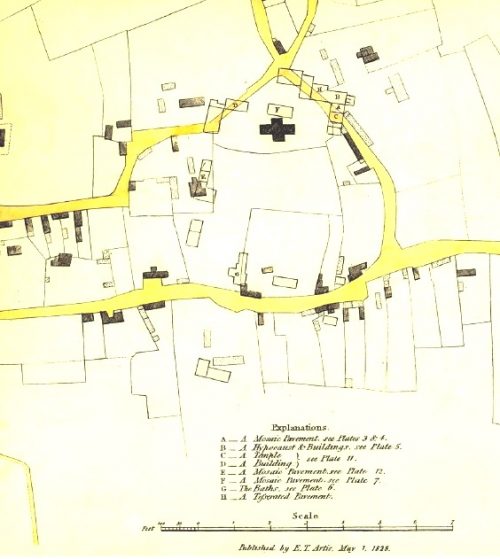

The first and arguably still the most important archaeological analysis of the Roman remains in Castor was made in the 1820s by Edmund Artis. He excavated a number of features and made impressive sketches of his finds.

The bath house marked “G” on the plan below

A view from the north-east of a room marked “B” on the plan below.

Intriguingly Artis even refers to Roman rooms ‘…the walls of which are beautifully painted and from 10 to 11 feet high.’

His village plan which locates the remains has been found to have some small mapping errors but is overall a reliable guide.

A number of smaller studies including one by Time Team in 2010 have filled in gaps in our knowledge of the site. However, the position close to the church, the church yard and the surrounding village constrain the opportunities for excavation.

You can still see the herring bone foundations of the Praetorium where the sunken roads around St Kyneburgha church cut through the walls of the building.

Finds from the site are quite plentiful but disparate given that only limited excavation has occurred in recent years. They include tesserae, painted wall plaster, coins and pottery. The earliest datable evidence from the main building is from the first quarter of the third century. The latest sealed deposits date to the very end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth centuries. There is nothing that helps define who occupied the building.

It appears that the structures south of the main building and lower down the slope were earlier – and may have been cleared when the main building was constructed.

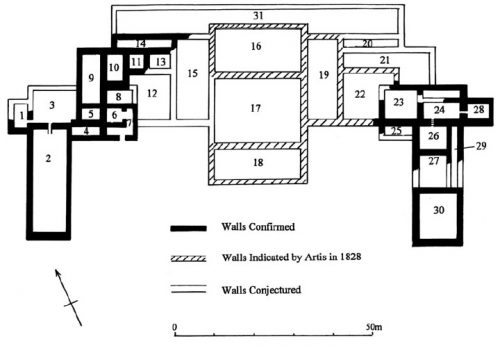

Stephen Upex has consolidated our understanding of the layout of rooms. Of particular interest are those forming the central entrance – rooms 18, 17 and 16. These echo the sequence of formal reception rooms at other sites such as Fishbourne. The scale of Castor Praetorium though is surprising: it appears to have the largest room known in a Romano-British residential building.

Reconstruction of the North Range with room numbering – Upex

In the post-Roman period the site appears to have had some element of continuity, for there is fifth-century pottery and later eighth-century occupation material from excavated contexts.

A nunnery was founded at Castor in the mid-seventh century by Cyneburgh (Kyneburgha), daughter of Penda who was the king of Mercia. The archaeological details of any such nunnery at Castor are very ill defined. No stone or wooden buildings have as yet been identified though it is possible that elements of the Roman structure were re-used.

That story of continuity can be extended to the current day. There is clear evidence of Roman building material in the walls of St Kyneburgha – and within the church there is the base of a Saxon cross with interlace decoration and dragons which was probably originally a pagan Roman altar.

Where did Castor Praetorium Fit?

The purpose of such a large building is still open to speculation. The favoured interpretation by Dr Stephen Upex is that it played a central role in the administration and taxation of the imperial agricultural estates of the east of England.

The fenland during the Roman period was a state-controlled area following confiscation of land after the revolt of the Iceni in AD 47 and the Boudiccan revolt of AD 60. A large stone structure was built at Stonea adjacent to an Iron Age fort. This seems to have been the initial focus for the administration of the new estates but it is believed that other administrative centres developed and Stonea was demolished in about 220AD. Durobrivae would have been an obvious choice given its good communications and urban growth.

Other suggestions include:

-

- A large villa

Much larger than others nearby. You need to look to Belgium, France and Germany to find villas of this scale - Military administrative centre

Perhaps the residence of the commander of the mobile field army, or of the British Saxon Shore - Guild of potters

There was a prosperous pottery industry and it is possible the complex was for a guild of pottery salesmen and their associates – or even a very wealthy owner

- A large villa

Why is the Castor Praetorium Important?

The sheer scale of the building makes it of national and even international significance.

But more than this, it clearly played an influential part in the Roman economy and life of the Peterborough area – and indeed of the more extensive Fenland region.