What is Norman Cross Prison?

Norman Cross Prison was constructed in early 1797 to house prisoners of the Napoleonic wars. It formed part of a network of military “depots” and with a capacity of nearly 7,000 it had a major impact on our sleepy, local towns and villages.

The 15 hectare site is to the east of the Great North Road (and now the A1) at Norman Cross, 5 miles from Peterborough and close to Stilton, Folksworth and Yaxley. A few fragments of the prison can still be seen, along with a field of lumps and bumps, and a memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died there before it closed in 1814.

Norman Cross was the first ever purpose built prisoner of war camp. Whilst only operational for 17 years, it drew national and international attention to the Peterborough area.

Norman Cross Prison – Evidence & Finds

As a military site the planning, construction, operation and dismantling of the prison are relatively well documented. In 1913 a history of the site was published by Dr Thomas James Walker, and in 2018 Paul Chamberlain provided an updated history inclusive of the personal stories of a good number of the inmates.

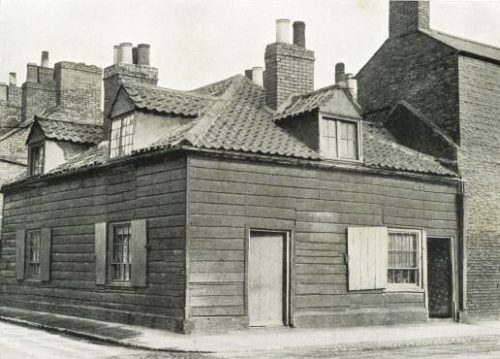

There is little of the prison itself remaining above ground other than a small section of the perimeter wall. Of the associated buildings, there is a substantial country house which was once home to the “Agent”, the senior administrator of the prison. The Norman Cross Gallery is housed in the garrison’s straw barn. Norman House, the Barrack Master’s house, also survives. The outline of the prison is visible in aerial photographs.

The former Agent’s House with section of perimeter wall behind

One of the cauldrons used for cooking prison meals is a water feature at the Elton Hall garden centre (closed at time of writing). And there are numerous examples of small objects such as domino sets crafted by the prisoners; Peterborough Museum has a collection of 800 such artefacts.

Time Team visited Norman Cross Prison in 2009. They focused on locating the prison’s cemeteries, a better understanding of construction methods, and post prison use of the site. The excavation helped verify the surviving prison plans but threw doubt on the theory that there was a separate “plague cemetery” to the west of the Great North Road.

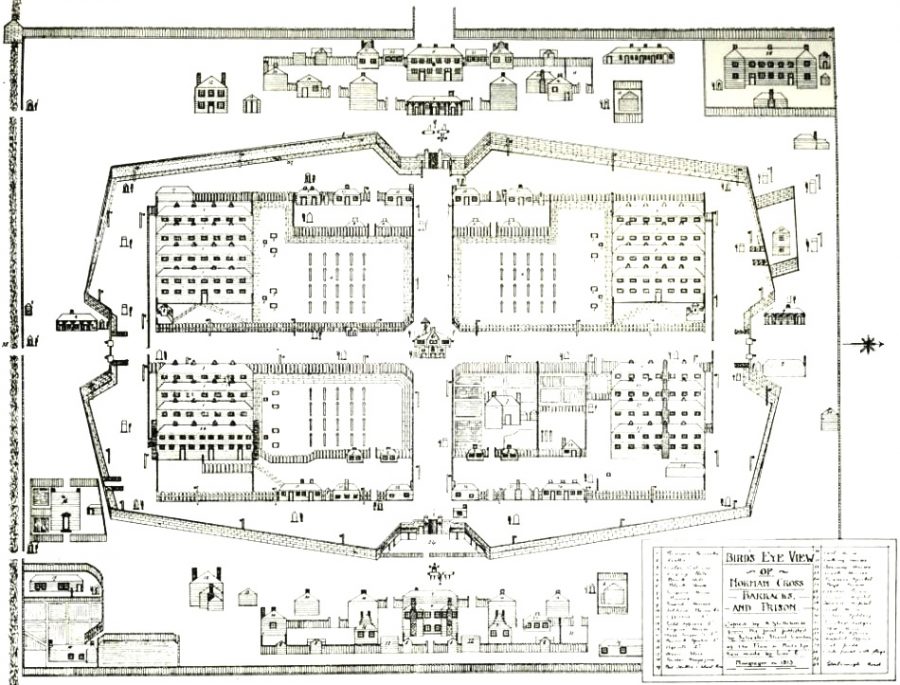

Site Layout

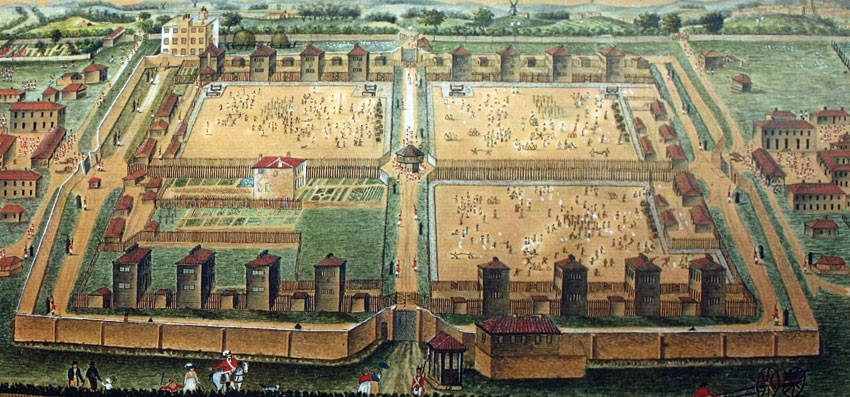

There were four quadrangles each secured with wooden stockade fences and separated by roadways. Each quadrangle comprised four 2-storey wooden accommodation blocks for 500 prisoners, latrines, an exercise yard, two turnkeys’ lodges, a store-house, and a cooking house. The north-east quadrangle contained the

Surgeon’s House (prison hospital). There was a central octagonal “block house” in which canon were mounted. There were guard towers around the perimeter which was defined by another wooden stockade fence – replaced in 1807 by a more secure brick wall. The prison itself measures about 250m by 270m. There were three entrances from the Peterborough road but the primary entrance was that from the Great North Road to the west.

Bird’s Eye View, East Elevation – Lieutenant E Magregor, 1813

The Blockhouse by Captain John Durant looking north-east with Surgeon’s House to the left. Prisoner in yellow

The site’s most prominent earthwork feature is the boundary ditch which was dug in 1809 to accommodate the ‘silent sentry walk’. The ditch was about 7m wide, 1m below the surrounding ground level, and 0.5m below a berm on the wall side. The camp roads which divided the open area into four quadrants are visible as faint raised strips of 7.5m average width.

Geophysical survey in the south-west quadrant in 2009, followed by trial trenching, located the buried building platform of one of the prisoners’ barrack blocks, measuring 32m by 11m, along with its associated latrine. Also found in this quadrant was the buried building platform of the punishment block, the baking house and a turnkeys’ lodge.

Time team Excavation – exposing the base of the “Black Hole” punishment block

The Time Team project also revealed a prisoners’ cemetery immediately to the north and east of the prison boundary. A range of finds contemporary with the camp was recovered including structural material (CBM, iron nails, window glass), domestic refuse (pottery, glass sherds, animal bone, marine shell), personal possessions (clay pipes, buttons, coins) and evidence for the prisoners’ craft activities (bone objects and bone-working debris).

Military barracks to both the east and west of the prison housed the militia responsible for security. Earthworks are visible on the west side of the camp, but those on the east side have been levelled by ploughing. The site of a soldiers’ cemetery consecrated in 1813 lies to the south-east of the former Barrack Master’s House.

Painting of unknown provenance – looking south

A Large Town

In 1801 the population of the nearby villages of Yaxley, Stilton and Folksworth was 986, 509 and 119 respectively. Peterborough’s population was already on the increase but was still only 3,500. The Norman Cross prisoner of war camp with a capacity of 7,000 inmates and 500 soldiers to guard them was to have a profound impact on the local area.

Initial construction took about four months from December 1796, with 500 carpenters and labourers constantly employed.

Contracts were put in place for the supply of large quantities of food, drink and fuel. The breweries in Peterborough (Buckle’s) and Oundle prospered; there was a daily beer allowance of 2 pints for prisoners and 5pints for soldiers. “Night soil” was removed daily.

Turnkeys, clerks and other staff were recruited from the local communities.

Prisoners from across Europe (and even further afield) were marched in their hundreds to and from Norman Cross following capture or agreement to their release or exchange. Many passed through Peterborough, reaching the Customs House on Fenland Lighters from Yarmouth and Kings Lynn. Others were marched along the Great North Road from the south. Captured officers were often paroled, staying in local towns including Peterborough.

Soldiers brought their wives and children with them, often regarding Yaxley as their temporary home. The frequency of marriages, baptisms and burials at St Peter’s Church all doubled during the operational period of the prison.

Commercial Enterprise

At the outbreak of the war, the Transport Board wrote that

“the prisoners in all the depots in the country are at full liberty to exercise their industry within the prisons, in manufacturing and selling any articles they may think proper excepting those which would affect the Revenue in opposition to the Laws, obscene toys and drawings, or articles made either from their clothing or the prison stores”.

Prisoners were given the opportunity to make and sell products. There was a regular market which at some periods seemed to allow fairly free interchange between inmates and the local population.

A contemporary account by Percy Blake observed

“Norman Cross presented less the appearance of a prison than a fair”.

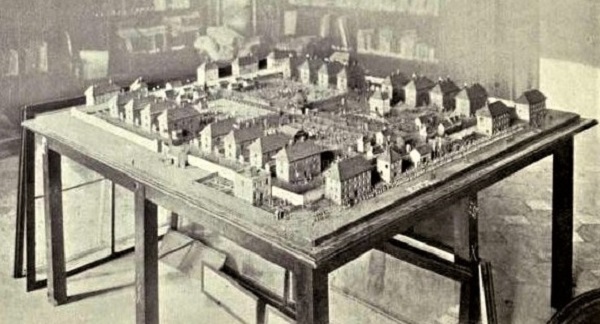

The skills of the inmates became well known. Artefacts such as toys, model ships and domino sets were carved from wood or animal bone. Artwork and straw marquetry were produced. Some prisoners were commissioned to produce special items with their wealthy patrons providing extra materials where needed.

At the end of the war, the Transport Board noted that some prisoners had earned as much as 100 guineas.

Jewellery Box, Tray and Games from the Burghley House Collection

The Palace Automaton – Peterborough Museum

Intricate model ship – Peterborough Museum

Model of the prison made by a French inmate photographed in 1913 at the Musée de l’Armée, Paris

Where did Norman Cross Prison ”Fit”?

The backcloth was what for a hundred years after was referred to as the Great War. Hostilities came to a head in 1793. War against first Revolutionary France and then a France under Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte continued until his overthrow in 1815. Virtually all European nations became involved and battles were also fought in the Caribbean, North Africa and the Indian Ocean.

As many as 200,000 soldiers and sailors were captured and brought to the UK. The greatest number were French but with Dutch and many other nationalities represented. The Transport Board of the Admiralty became responsible for handling these captives. There was a rapidly expanded network of receiving prisons, prison ships, parole depots and Land Prisons. Norman Cross was the first of three purpose built inland “depots”; the others were at Dartmoor (1809) and Perth (1811).

Looking after prisoners of war was a drain on resources but care was taken to treat inmates well, not least so that the same might apply to Britons held overseas. There was extensive communication between the warring parties and during much of the conflicts there were regular prisoner exchanges.

The last prisoners left in 1814. The wooden buildings were dismantled in June 1816 and the parts sold at auction. Some of the buildings were relocated to nearby towns although much of the timber structures were sold as firewood.

One of the turnkeys’ lodges – St Leonard’s Street, Peterborough

A memorial to the 1,770 prisoners who died at Norman Cross was erected in 1914 by the Entente Cordiale Society beside the Great North Road. Its bronze eagle was stolen in 1990, but replaced with a new one in 2005 on the re-sited column.

Unveiling of the Norman Cross Memorial alongside the Great North Road, Tuesday 28th July 1914

Why is Norman Cross Prison Important?

As the world’s first specially constructed prisoner of war camp, Norman Cross Prison was a prototype for the future development of military prisons.

The earthworks and buried remains have been little disturbed and can help build a rich appreciation of the life of prisoners, soldiers and civilians during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic War period.

More Information about Norman Cross Prison

Wessex Archaeology Excavation Report (Time Team)

Time Team Excavation Video

Historic England – Norman Cross Listing

Walker, Thomas James. The Depot for Prisoners of War at Norman Cross, 1913

Peterborough Museum – Inventory of Artefacts

Chamberlain, Paul. The Napoleonic Prison of Norman Cross, 2018