Several new members joined the FRAG tour of Stonea Camp and Stonea Grange led by David Crawford-White on Saturday 9th September.

The lumps and bumps reveal little on their own but with David’s expert commentary we gained a good understanding of their significance. The late Iron Age “hill fort” lying just a couple of metres above sea level may well have been the scene of an important battle with the recently arrived Romans. The nearby Roman building was probably designed to impress and control the defeated locals.

As well as exploring the large Stonea site, David brought along a range of relevant artefacts – and after lunch we visited the March & District museum.

Stonea Camp – Summary

The multivallate fort dates from the late Iron Age – about 150BC.

There are a series of “D” shaped banks/ditches which have been attributed to either 3 or 4 phases of construction.

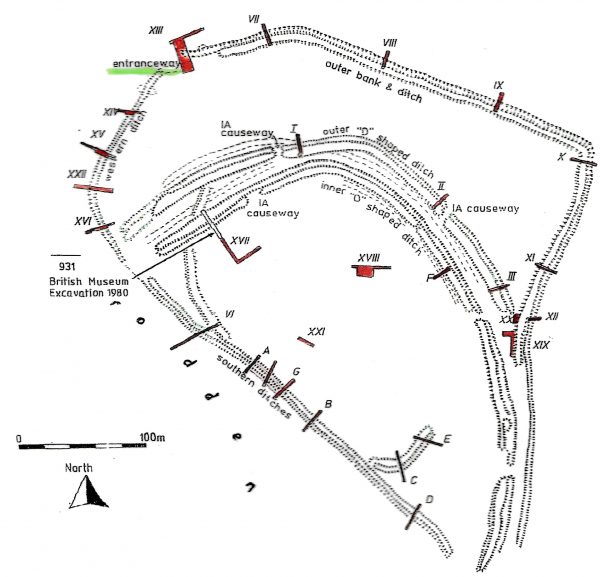

Location of trenches – Malim, 1992

The fort was close to the boundary of the Iceni, Catuvellauni and Coritani tribes. There is no real evidence for domestic settlement on the site and it is suggested it may have been used on a periodic basis for defence or as a meeting place.

Although partially damaged by a modern quarry near the south- eastern corner of the monument and despite several years of cultivation in the post war period, a large area of the interior contains evidence relating to the use of the site in the Iron Age. Finds include late Iron Age and early Roman pottery, and metalwork in the form of bronze brooches, and gold and silver coins. Coins from several Celtic tribes have been found at Stonea, which is considered unusual.

The most recent major excavations were undertaken from 1990 to 1991 by Tim Malim focusing on the banks and ditches of the fort. These features were easily identified by soil marks and crop marks enabling trenches to be located over them and sections excavated. In some cases the basal fills were waterlogged, increasing the preservation of organic remains. Several skeletons of adults and children were found including the skull of a 4 year old, cut twice by a sword: perhaps a victim of the Roman battle.

In 1991 a programme of restoration took place: the modern material used to infill the ditches was excavated in a controlled manner and used to reconstruct the banks, so that the appearance of the monument is much as it was in the 1940s.

A Bronze Age barrow lies to the east of Stonea Camp. Excavated in 1961 this contained a cremation burial of a high status female, with grave goods including 17 Jet and 11 amber beads from the Baltic, as well as pottery and flint objects.

Iron Age Fenland

The fen landscape was very different in Iron Age and Roman times. Rivers meandered through the marshy low lying land – around a number of islands which were just a few meters higher. Stonea was one such island; there was another small island where Manea is now located and larger islands which correspond to March and Chatteris.

There is plenty of evidence of Iron Age occupation of this higher land which would have had attractions in terms of defence, transport and a plentiful food supply. This was a time when society became more complex, tribal groupings arose and territory, landownership and conflict increased.

From the Middle Iron Age (500 BC+) a great number of defended settlements were constructed across Britain, and ritual or symbolic centres were appearing throughout the landscape. Hilltops were favoured locations but the Stonea site has parallels with those forts found elsewhere. It is assumed that the Stonea fort would have had a continuous 2m high oak palisade around its perimeter.

Roman Attack at Stonea

Stonea is believed to be the site of a major battle between the conquering Romans and the Iceni tribe. Led by their queen, Boudicca, they had major successes against the invaders in 60-61AD with attacks on Colchester, London and St Albans.

Stonea corresponds with a site in the east of England described by Tacitus where the Romans overwhelmed local fighters who were “imprisoned by their own defences”.

Stonea Grange

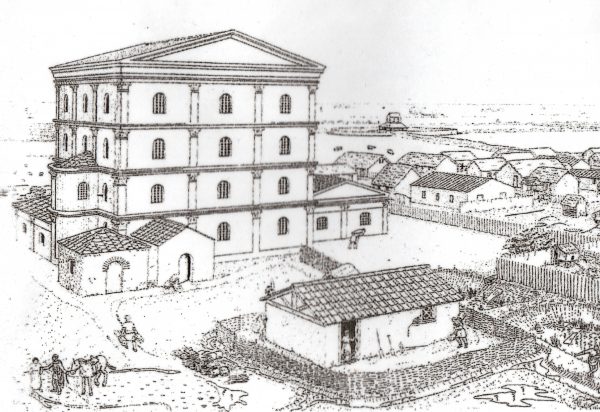

Just to the north of the Iron Age fort there is archaeological evidence for a major Roman municipal building. The foundation walls suggest a building of perhaps 4 stories, and alongside there was a small settlement and a temple.

© British Museum – Simon James

The scale of “Stonea Grange” suggests an imposing administrative complex playing a central role in the subjugation of the rebellious local community. The Romans started to drain the marshy fenland and ran the area as an imperial estate.

March & District Museum

March museum includes a small section relating to Stonea but its charm is really in its eclectic mix of local artefacts from prehistoric to post war times. It is housed in an 1851 school house, conveniently close to free car-parking and a friendly pub (Georges).

More information about Stonea Camp