About Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling

There are many aspects of Peterborough Cathedral which are both awe inspiring and testament to the skills and imagination of our medieval ancestors. However, the nave ceiling is arguably the ultimate jewel within the cathedral.

The painted wooden ceiling dates from the first half of the 13th century and is the only one of its type surviving in Britain. It is the largest of only four wooden ceilings of this period surviving in the whole of Europe. It has been overpainted twice but retains its original style and pattern.

There is little contemporary documentation relating to the nave ceiling so understanding of its history is heavily dependent upon examination of the surviving structure and its decoration.

Unlike many of our other local treasures it is highly accessible, free of charge and only 5 minutes from the city centre shops!

Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling – Evidence & Finds

Concerns were being raised about the condition of the Nave Ceiling by the 1990s and this prompted a period of first investigation then conservation. The fire of 2001 then inflicted smoke damage necessitating further intervention. The upshot is that the ceiling is in better condition than it has been for many centuries, and we have a wealth of published and archived information about its history (see Hall and Wright 2015).

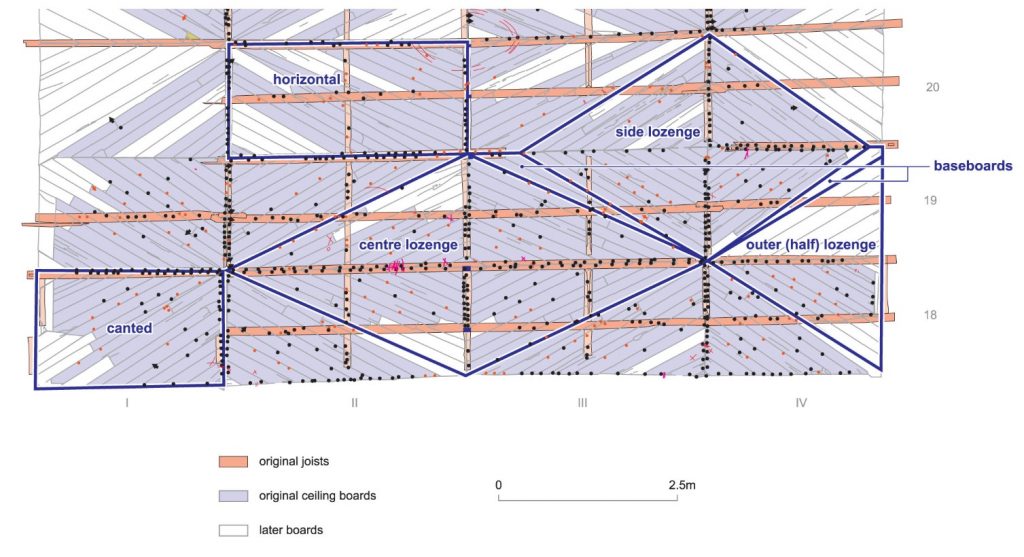

The 62m x 11m ceiling is largely original, constructed from boards nailed clinker-fashion directly to the underside of the joists and noggins. It is suspended 25m above the nave floor. The roof structure which supports it dates from the 1830s when Edward Blore replaced the original oak beams. As well as this work we know that the ceiling is likely to have been affected by re-building of the tower in both the 14th century and the 1880s.

The ceiling comprises four rows of 40 panels. The central rows are horizontal and the outer rows are inclined (canted). There is also a vertical section of painted boards at the sides. The boards are arranged to form a series of diamond shaped “lozenges”, each containing a unique image. There are three sizes of lozenge with the largest being in the central row.

A section of nave ceiling structure showing arrangement of boards, panels and lozenges, Copyright © Harrison and Lithgow (Hall and Wright 2015, fig 70)

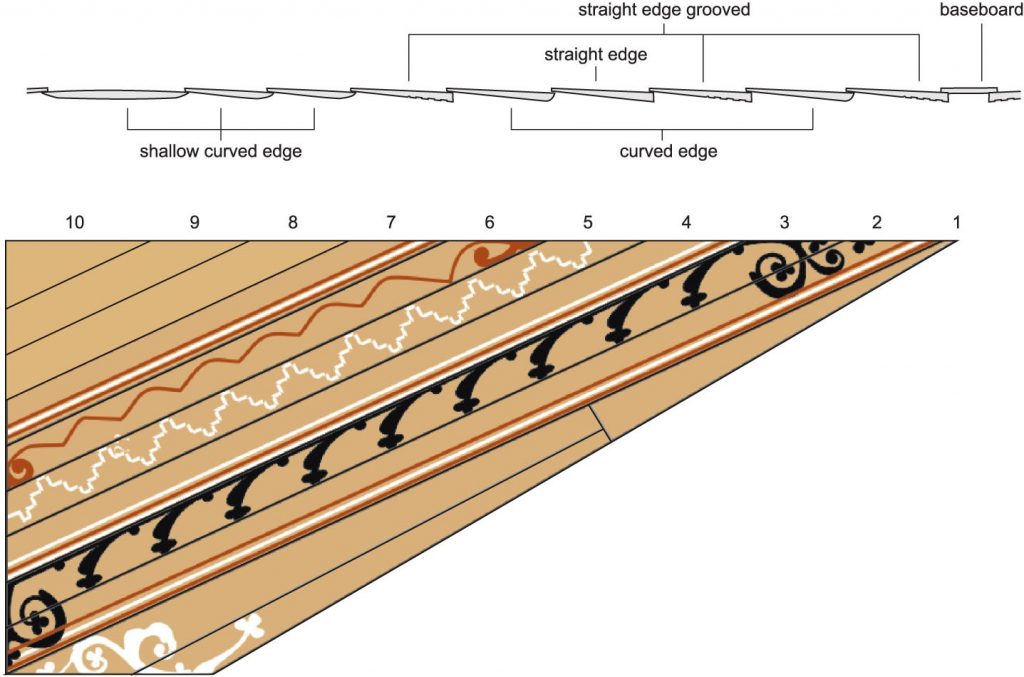

The original boards are riven or cleft oak and mostly have a tapered section. The boards are on average 200mm wide, and with a thickness of 15-22mm on one edge, and 3-9mm on the other. Average length is about 2250mm. The “base boards” around each lozenge are flat in section. The differing edge profiles are designed so that the picture in the centre of each lozenge would not be distorted.

A proportion of the boards were either repositioned or replaced with soft wood during the two periods of renovation. Of about 2170 boards it was found that 34% had been replaced.

A typical lozenge showing the sequence and arrangement of different board sections, Copyright © Harrison and Lithgow (Hall and Wright 2015, fig 100)

The original nails to secure the boards are round headed, approximately 18mm in diameter, with small square shanks, and 65mm in length. In the 1830s restoration a system of wrought iron hanging bolts was introduced to suspend sections of the ceiling.

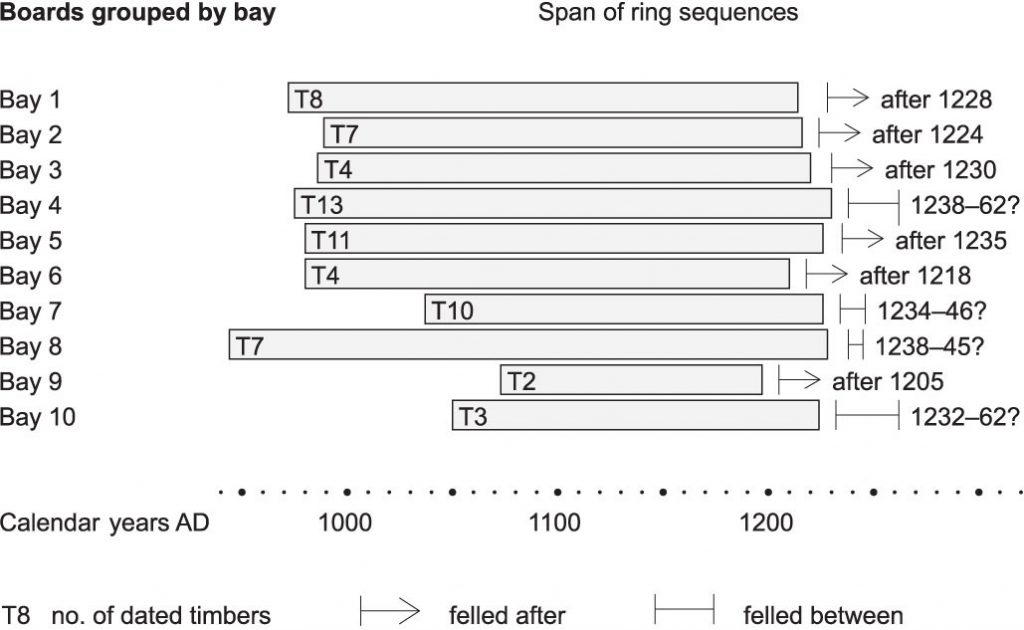

It was hoped that dendrochronology would provide precise dating for the ceiling. Many timbers have been analysed but there are few which include the heartwood/sapwood boundary which would enable greater accuracy. However, we do know that the oak used in the original ceiling was from mature trees which had been growing in the 12th century in what is now northern Germany. The trees were felled in the 13th century with the latest being no earlier than 1238. The most likely conclusion is that the construction of the ceiling took place in the late 1230s and the 1240s.

Tree-ring dating of nave ceiling by bay, Copyright © Tyers and Tyers (Hall and Wright 2015, fig 93)

Art historian, Paul Binski, has assessed the style of the design compared to other artwork of this period such as the Peterborough Psalter. The ceiling fits firmly within the 13th century – and most probably in the second quarter.

The painting of the ceiling follows the arrangement of ceiling boards with three interlocking rows of “lozenges” each with a figurative design at its centre. The 40 larger images in the central row include an alternating sequence of 6 kings and 5 bishops (or archbishops), as well as representations of St Peter, St Paul and the Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God”). Other themes include the “liberal arts”, “musicians” and “vice”. There are also many foliate designs.

The 7 Liberal Arts – grammar, rhetoric, logic, music, geometry, arithmetic, and astronomy, Copyright © Historic England (for Hall and Wright 2015, figs 120 and 121)

During conservation it was discovered that the original paint was present beneath the original nail heads. This helped establish that all the boards were painted before being fixed into place.

The original paint layers are all oil based. The pigments used such as red ochre, yellow iron oxide and lead white are consistent with those identified with other early English panel paintings.

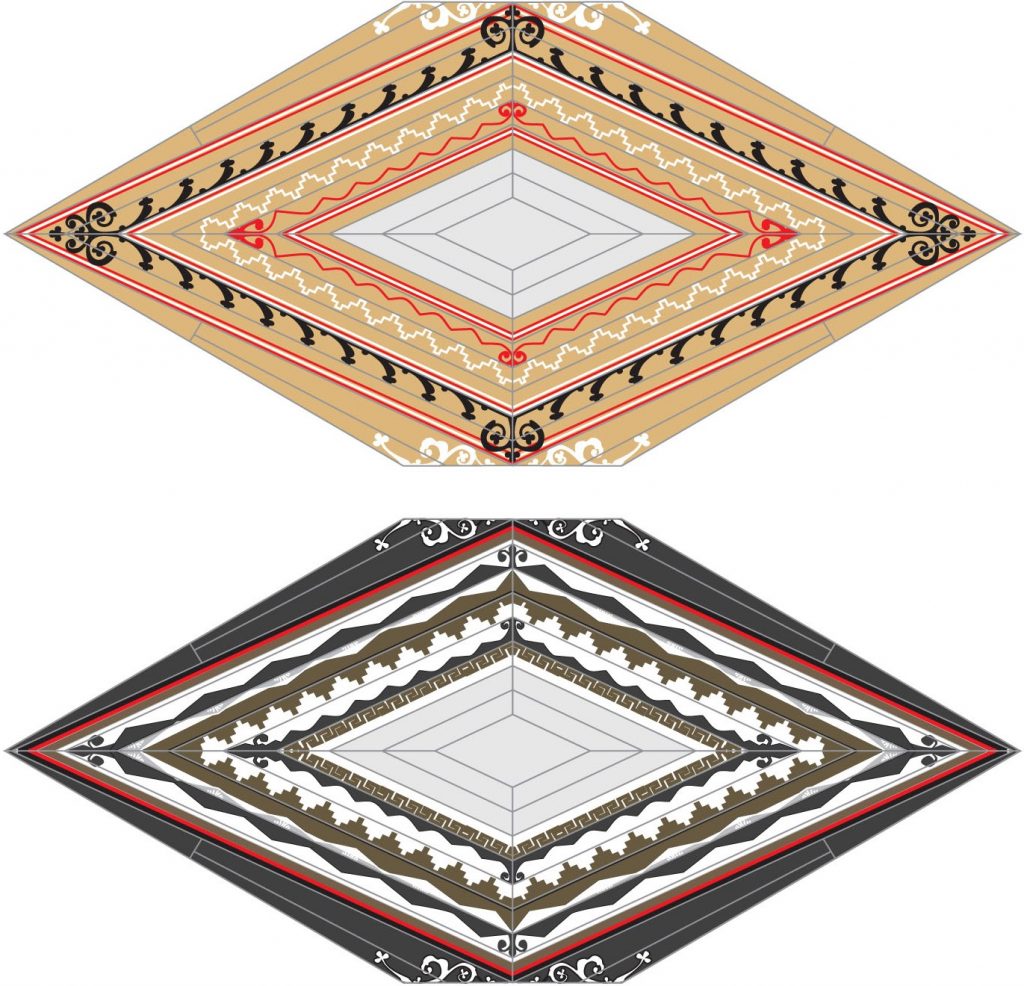

The boards surrounding each image are painted with a sequence of borders which accentuate the diamond shaped compartmentalised design. In contrast to the images themselves, the pattern of the border design was changed significantly when the ceiling was repainted in the 18th century.

Reconstruction of the 1740s/1830s border design (bottom) compared with the original, 13th-century, decoration (top), Copyright © Harrison and Lithgow (Hall and Wright 2015, fig 133)

There is documentary evidence of re-painting in the 1740s and the 1830s, though no detailed records of these restorations. Lithgow and Harrison suggest “repainting on both occasions was extensive and inept.” He also notes that “the restorers in the main followed closely the original foliate and figurative designs on the central boards of the lozenges, although the original lozenge border designs differ significantly from the present scheme.”

An exception to fidelity to the original design was the current image of a dragon where it can be seen that part of the original image featured a fox.

The faint outline of the original figure of a fox highlighted in red, Copyright © Harrison and Lithgow (Hall and Wright 2015, fig 98)

Where did Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling “Fit”?

A Benedictine Abbey was created at Peterborough in the 10th century. Ancillary buildings were destroyed in Hereward the Wake’s resistance to the Norman takeover in 1069, but the church survived until an accidental fire swept through it in 1116. The present building was begun in 1118 and we know from dendrochronology that the main roof structure of the nave probably dates to the 1180s. The transept clinker built wooden ceilings of the early 13th century were effectively prototypes for the larger nave ceiling which followed.

The church was first consecrated in 1238 but decorative aspects were not fully completed by that date. It seems likely that the nave ceiling was installed in the late 1230s and 1240s. This corresponds to the abbacy of Walter of Bury St Edmunds (1233-45) who also oversaw the construction of an extended choir within the nave.

Ornate painted ceilings were highly prized in the Romanesque period before the advent of rib vaulting. The compartmentalised, interlocking design echoed a style sometimes seen on Roman mosaic floors and walls. The style of the design is consistent with contemporary artwork of this period, and not least the stunning images contained in local works such as the Peterborough Psalter. The choice of topics represented reflects a humanistic Benedictine culture in the south and east of England (not least, the inclusion of the Liberal Arts, images of vice, and the sun and moon in chariots).

The oak for the earlier roof structure and for the transept ceilings was sourced locally. So it is of real significance that for the nave ceiling it was deemed necessary to source wood from northern Germany. The large volume of long thin planks required could clearly not be met from dwindling local supplies. Importation of timber from the Baltic via the Hanseatic League became commonplace from the early 14th century but the example of the Peterborough nave ceiling is one of the earliest known of large-scale import from the north of Europe.

Why is Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling Important?

Peterborough nave ceiling is truly unique. There are other painted ceilings from this period in Switzerland (St Martin’s, Zillis, c1150), Germany (St Michaels, Hildesheim, c1200) and Sweden (Dädesjö, Smaland, c1275) but none is as large nor as well preserved.

Of the painted decoration Binski suggests: ‘it stands with a very few other English instances of painted vault or Ceiling decoration: the overpainted mid 13th- century choir and presbytery vaults at Salisbury Cathedral; the (lost but recorded) paintings of c. 1220 on the vaults of the Trinity Chapel at Canterbury cathedral; the late 13th-century wooden painted vaults of the presbytery at St Albans; the Chapterhouse vault at York Minster; and the (secular, but adorned with religious subject-matter) Ceiling of the Painted Chamber in the Palace of Westminster of c. 1263’.

The Peterborough ceiling provides deep insights into:

- Design and methods of construction

- Materials and their sources (from paints to timber)

- Art history

- Ecclesiastical beliefs and symbology

- The growth, wealth, and importance of the Abbey at Peterborough

More Information about Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling

Conservation & Discovery: Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling & Related Structures. Jackie Hall & Susan Wright (editors). MOLA, 2015

Copies available from the Cathedral Shop and from MOLA

Peterborough Cathedral Nave Ceiling Conservation – Project Documents, Julian Limentani, Gillian Lewis, Richard Lithgow, Cathy Tyers, Tobit Curteis, Paul Bryan, Ian Tyers, Hugh Harrison. Archaeology Data Service

The multi-million pound Nave Ceiling conservation project necessitated a team of experts including paint and wood conservators, art historians and archaeologists, dendrochronologists, environmental specialists and archivists. An appeal fund by the Cathedral was further supported by major grants from Historic England (then English Heritage) as well as from the Pilgrim Trust and the Cripps Foundation.