What is Must Farm?

At the Must Farm excavation site between Peterborough and Whittlesey archaeologists have uncovered one of the best preserved settlements dating to the Late Bronze Age (1000 – 800BC).

Initial excitement had been generated by the discovery of log boats, fish traps and a wooden platform. Full excavation has now revealed 4 roundhouses and their domestic contents in extraordinary detail.

Perhaps as little as six months after the settlement was built , the houses had caught fire and collapsed into the mud and water below – “A Bronze Age Pompeii”.

The site was exposed as a result of the extraction of clay for brick production by Forterra (formerly London Brick and then Hanson). The excavations undertaken by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) have been funded by Forterra and Historic England.

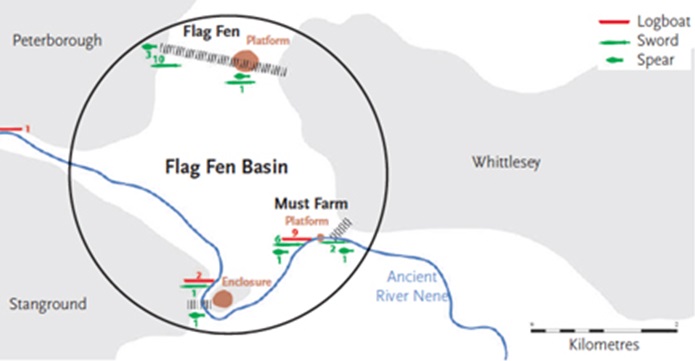

The site is within 3 miles of Flag Fen and was constructed as the earlier Peterborough to Northsea causeway was in decay.

Must Farm and the Flag Fen Basin

Must Farm – Evidence & Finds

In 1999 decaying timbers were discovered protruding from the southern face of the brick pit at Must Farm. Investigations in 2004 and 2006 dated the timbers to the Bronze Age and identified them as a succession of large structures spanning an ancient watercourse.

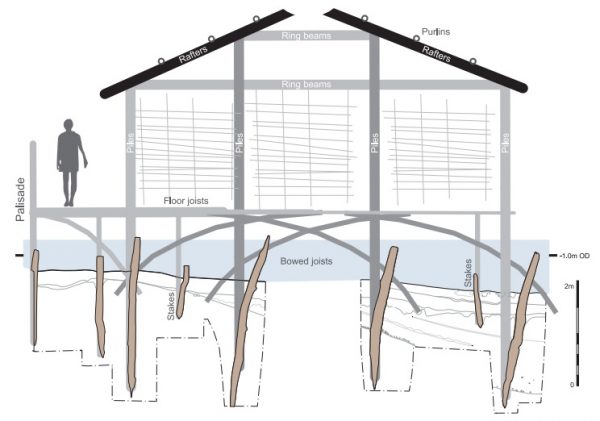

The settlement consisted of houses built on a series of piles, or stilts, sunk into a river channel below. Around the edge of the settlement was a palisade constructed from large ash posts. It appeared that about half of the settlement had been removed by quarrying in the 1960s but that the remaining half retained the remains of perhaps 5 round houses.

The timber structures were wet when they were in use and wet for a long period afterwards providing excellent conditions for preservation of organic objects as the layers of silt accumulated.

Once it became clear that the remains would be endangered if left in situ a more comprehensive excavation was undertaken in 2015 and 2016. This allowed a forensic investigation of the site and the unearthing of a wealth of everyday objects.

There were thousands of finds and their analysis was finally published in 2024. (A publication on the log boats is still awaited.)

Some of the highlights:

- The uprights and roof timbers of 3 roundhouses – lying as they fell when the site burned

- Nine log boats

- A complete wooden wheel

- Fabric yarn wound onto bobbins

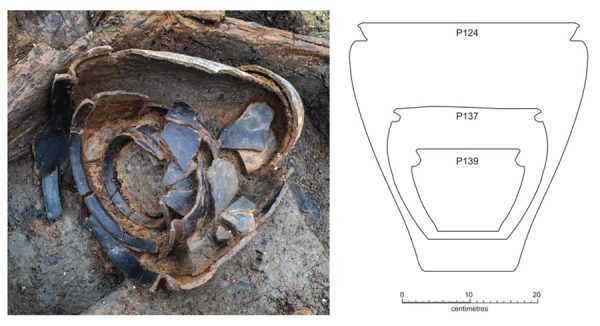

- A nested set of pots

- Wicker fish weirs and fish traps

- Pots – still containing food

Must Farm – Log Boat.

Must Farm – Wheel

Must Farm – Bobbins

Must Farm – Nested Pots

Must Farm – Eel Trap

Must Farm – Pots

Where did Must Farm “Fit”?

This was a period of rising sea levels and encroachment of lands which had previously been dry. We are seeing a community which is adapted to life at the fen edge – with access to wood, crops and animals from dry land, but making skilled use of the neighbouring waterways.

This settlement is likely to be one of many along the course of the River Nene at this time – and it is close to the earlier Flag Fen platform and causeway which is interpreted as having ceremonial significance.

The houses and their contents are entirely consistent with other scattered evidence across Britain from this period. So although the quantity of objects is unique it is likely that we are gaining a glimpse into typical everyday Bronze Age life.

Why is Must Farm Important?

It is the depth and waterlogged nature of the site which make Must Farm so important. Objects which would normally have decayed or have been destroyed by agriculture and subsequent development have lain undisturbed.

The settlement has yielded the largest collection of domestic metalwork from Britain, including axes, sickles, gouges and razors.

Must Farm has the largest, and finest, collection of textiles from the British Bronze Age.

These extremely delicate objects were preserved by the unique combination of charring and water logging resulting from the destruction of the settlement.

Duncan Wilson, chief executive of Historic England:

“A dramatic fire 3,000 years ago, combined with subsequent waterlogged preservation, has left to us a frozen moment in time, which gives us a graphic picture of life in the Bronze Age. This site is of international significance and its excavation really will transform our understanding of the period.”

More Information about Must Farm

Must Farm Pile-dwelling Settlement – 2024 Report

Vol 1: Landscape, architecture and occupation

Vol 2: Specialist reports

Must Farm Website

Historic England – Must Farm

Antiquity. Volume 93, Issue 369 June 2019 , pp. 645-663

MUST FARM – FAQs

Now the Must Farm Reports are published, we can use them to attempt answers to some “Frequently Ask Questions” – though as ever, there is much left to investigate and piece together!

How was Must Farm discovered?

“Sharp eyes and a curious mind” is the simple answer. The Must Farm excavation was triggered by local archaeologist, Martin Redding, who in 1999 spotted some aligned posts, poking up at the edge of a then water-filled brick pit. When the owners decided to recommence extraction the need to evaluate and then excavate the site became imperative.

Image credit – Ben Robinson

The Must Farm Quarry was in fact first opened in the late 1960s and finds had included a Late Bronze Age rapier and a sword, as well a quantity of potsherds (reconstructed into whole pots and held by Chatteris Museum). In retrospect, these can be linked to the Must Farm settlement. Unfortunately, the earlier quarrying is thought to have removed evidence of at least a further two roundhouses.

How do we know the site was occupied for less than a year?

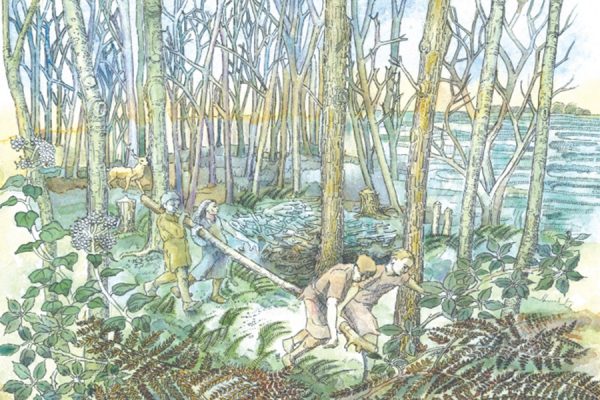

There are a variety of clues, but the most compelling evidence comes from the wood used in construction.

The majority of wood used for construction was sourced from a single patch of woodland with young, straight ash and oak. It is likely to have been located in low contour fen woodland relatively close to the construction site. Dendrochronology indicated that the trees were felled during the autumn/winter.

Reconstruction of fen woodland exploitation. Image: J. Dobie

The lack of extensive burrowing by ash bark beetle, or any of the multitude of British bark beetle species, constrains the likely duration of the pile-dwelling settlement to at most two years, and more probably a single year.

The fact that much of the wood was unseasoned, and that the quantities of rubbish associated with habitation were limited, also point to the short life of the settlement.

A consequence of the site’s short period of occupation and sudden demise was that the stratigraphy was very shallow (150 to 350mm), comprising only three main layers (relating to construction, occupation and destruction).

What did the Must Farm people have in their homes?

We like to label prehistoric people by the few pottery or metal objects we normally find, but at Must Farm we can relate to the much wider variety of household stuff and clutter with which we ourselves are familiar.

The occupants of the stilted settlement fled hurriedly and many of their belongings fell immediately into the muddy waters below. For practical, or maybe reasons associated with their beliefs, they were unable or unwilling to recover even the metal objects. Not all their possessions will have survived – but far more than we have found anywhere else.

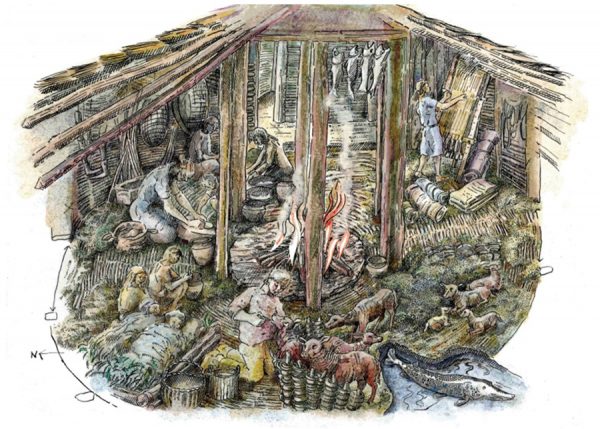

Reconstruction of a house interior from the Must Farm settlement. Image: J. Dobie

Each house would have included a central hearth surrounded by specialised spaces for functions including cooking, sleeping, care of small animals, and fabric production.

Houses contained culinary equipment (pots, stirrers, scoops, chopping/serving boards, troughs and buckets) tools (sickles, gouges, axes) and textile-related paraphernalia (loom weights, spindle whorls, plant fibre bundles and sticks of yarn).

Archaeologists were able to divide the pottery finds into those which were broken and discarded, and those which were in active use. The latter (“living assemblage”) comprised 64 vessels, dominated by fineware bowls and cups, with a smaller number of coarsewares. It is a service geared to family cooking, dining and consumption.

The living assemblage accounted for only 75% of the pot sherds found (by weight). This implies that breakage rates were extremely high (over one pot per week), suggesting pots were seen as disposable, short-lived utensils, despite the skill and time invested in their production.

Three collapsed, but complete, nested vessels. Image: CAU

Grain stores were identified, and fragments were found from at least six possible quernstones. Three of these are traditional saddle querns, comprising slabs of sandstone, dolerite and granite, respectively.

Fibres and fabrics were in production at the site. These were all from plant fibres, predominantly flax. Finds included more than 35 neatly formed bundles of flax fibre strips. Processed fibre was spun into 2 or 3 ply thread and wound onto wooden dowels or into balls; there were 36 wound bobbins as well as a cone of thicker cord.

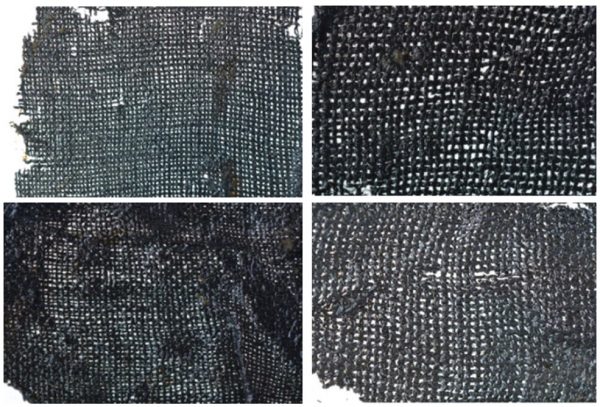

Woven fabric from Must Farm. Image: CAU

The distribution of tools and weapons across the settlement’s structures suggests there might have been a standard “baseline tool set” (per household or even per craftsperson) comprising a mid-sized general purpose ribbed axe, a smaller general purpose facetted axe, a gouge or chisel, and probably a sickle.

Socketed axe with two-piece haft. Image: CAU

The range of sickles discovered emphasises that this was a farming community which was growing crops on dry land as well as hunting and fishing.

Varied forms of sickles from Must Farm. Image: CAU/Uckelmann

Small metal pieces and broken bronze objects found in a wooden bucket were almost certainly being prepared for re-casting or for exchange for other goods.

Collection of ‘scrap’ metalwork with broken wooden container. Image: CAU

What did the Must Farm people eat and drink?

Many of the pots and wooden vessels had sufficient food, or residues of food, to provide information about Bronze Age cookery and diet. This is further elaborated by analysis of discarded bones and of faeces. Perhaps, the most striking discovery is the quantity and range of wild animals, wild fowl and fish consumed.

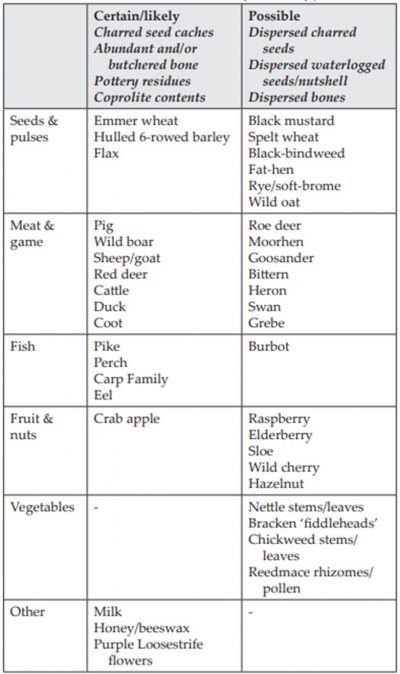

Source: CAU Report Vol1

The pot residues point to the porridges, stews, brewing mashes, doughs, and sugary or oily liquids, which were being stored (or potentially even being eaten or drunk) at the time the settlement burnt down.

Coarseware ceramic bowl containing gelatinous wheatmeal stew/porridge and a wooden spatula. Image: CAU

Tentative brewing mashes suggest the possible production of a form of beer, with beeswax lipids suggesting use of honey as a sweetener. If so, the closest analogy for the finished product is probably boza – a thick, mild, lacto-fermented grain-based drink still made in parts of southeast Europe and western Asia.

What happened to the Must Farm people?

Apart from one human skull (which may have been that of a previously deceased family member) the excavation did not find human remains.

It is feasible that the community came under attack from elsewhere and were taken away, but more likely that they had just sufficient time to flee to a safe place as they watched their hopes, dreams and a year’s labour go up in smoke.

Footprints and hoofprints in Surface 5 of the river silts (Image: CAU)

Were all the structures the same?

There was one rectangular building, but the four roundhouses fully or partially investigated were all of a similar design and construction. All structures were domestic.

They were very tightly grouped and it seems likely that they represented the combined home of an extended family. There were some commonality in the way each of the buildings was used and, for instance, pottery analysis points to independent living.

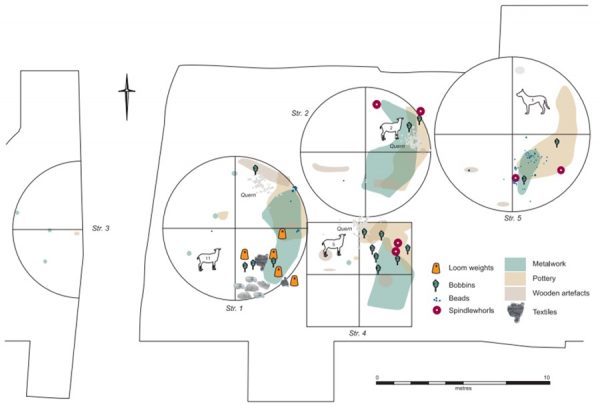

Equally there seemed to be some specialisation. For instance, sheep were present in three and dogs in only one house. Flax was probably being processed in Structure 1, with the spinning of fibres into yarn taking place across Structures 2, 4 and 5, before finally being woven into textile on the warp-weighted loom located back in Structure 1.

Perhaps some activities were undertaken independently and some collectively with differences between houses reflecting seniority or age.

Must Farm use of space – distribution of key materials and faunal groups. Image: CAU

Was it a special, high-status community?

With a sample size of one it is tempting to consider a site such as Must Farm (over water and with such a range of artefacts) a special case – perhaps a particularly wealthy community.

The community clearly had the resources to build an impressive structure in quite a short period of time but, in many other respects, they were carrying on the kind of lifestyle which had probably been typical at the Fen edge for hundreds of years. There was higher than anticipated consumption of domestic wares and food but no suggestion of feasting or supra-household congregation.

Bronze spearheads and amber beads are often seen as high-status objects, available only to a few, but the evidence from Must Farm opens up the possibility that many more people had access to such things, and that their relative rarity in the archaeological record is the result of poor preservation and practices such as recycling.

Reconstruction of the Must Farm Bronze Age village. Image: CAU

Was it a self-sufficient subsistence community?

The Must Farm occupants were capable farmers, fishermen and hunters, with wood, metal working and textile skills. However, there is plenty of evidence that they did not live isolated lives and were ultimately dependent on a range of relationships in the world beyond.

For a start, they were dependent on wood, cereals, and other plants which came from the neighbouring dry land. They would have had rights to use areas of land, probably in association with nearby communities, for crops, grazing, forestry and hunting.

There was only limited space for “agricultural processing” on the platform. It is clear, for example, that butchery was undertaken elsewhere, and only select joints brought into the houses.

Woodworking is an area where there was perhaps a divide between the everyday skills of the local people and more specialised skills needed for certain items. The absence of neat joints in the structure of the roundhouses contrasts with the sophisticated joinery of the wooden wheels.

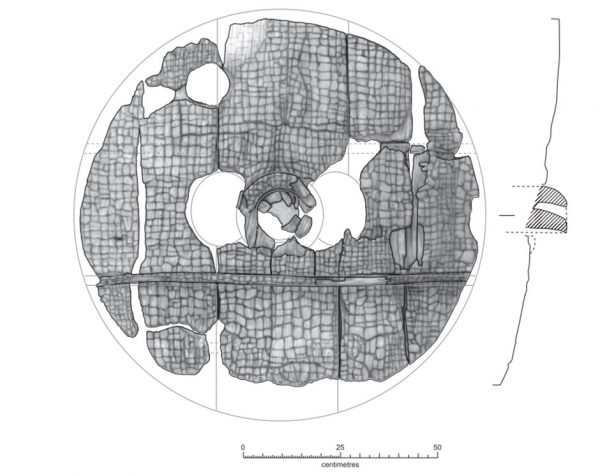

A Must Farm Tripartite wooden wheel made from cleft alder boards jointed together with dowels and dovetailed braces; they had integral hubs, each decorated with a relief-carved vertical strip. Image: CAU

Some of the metalwork was produced locally but other items were from further afield, including a bronze bucket found to originate from Ireland. And jewellery came from even further away.

Over 56 beads were discovered. Their bright colours and sheens would have been striking amongst the browns and greens of the settlement. Analysis shows multiple glass beads were from Iran, a tin bead from central Europe, an amber bead from Scandinavia and shale beads from Kimmeridge.

Whole beads of various materials. Image: CAU

Reconstruction of a necklace featuring amber, shale, siltstone and glass beads. Image: CAU

One question this interconnectedness begs is why the defensive ash and oak palisade? This is thought to have surrounded the whole settlement and may have involved the piling of over 400 close-set timbers with a continuous flanking walkway along the interior perimeter. A commitment to defence which is not usually evident at other Late Bronze Age sites.

Were the round houses like those on dry land?

Archaeologists are keen to determine to what extent they can rely on the evidence from Must Farm when interpreting Late Bronze Age settlements and round houses found on dry land. This is likely to be a continuing debate but in many ways the Must Farm findings are reassuring.

Schematic elevation drawing. Image: CAU

There are obvious differences when construction is on piles over water, but the pattern of build and occupation is familiar. At about 8m, the diameter of the roundhouses is similar to those on dry land. There are two concentric rings of posts supporting the roof (albeit that the Must Farm inner ring has a smaller diameter, perhaps to help carry the raised hearth). There is no obvious doorway and porch identifiable at Must Farm but spatial use points to a southeasterly orientation as is often the case elsewhere (areas receiving less light are used for activities such as sleeping).

The Must Farm dwellings lacked daub on their wattle walls; roofing was with turf, clay, and possibly thatch. These features differ from most reconstructions of Bronze Age roundhouses to date but may simply mean that our previous assumptions need to be challenged.

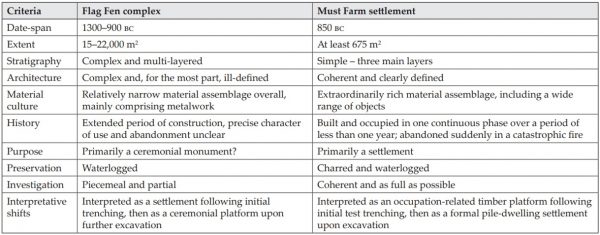

How does Must Farm relate to the neighbouring site at Flag Fen?

The Flag Fen Basin has been one of the most analysed Bronze Age locations in Europe over the past 50 years. Two major sites for Peterborough archaeology are just 1½ miles apart. But care is required in making connections.

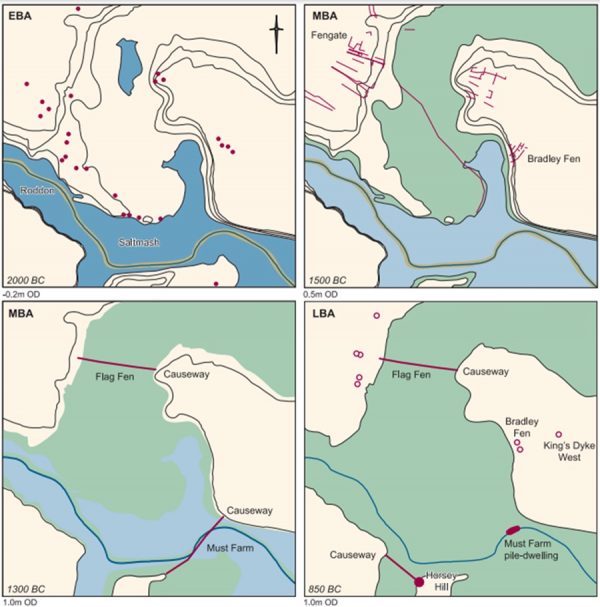

Flag Fen appears primarily to be a causeway connecting the mainland to an island created by rising water levels. In fact there is evidence of another Middle Bronze Age causeway which bridged the river and traversed the surrounding fen, near Must Farm. The later pile dwelling settlement lay on its path, and its rotting timbers would have been evident when the hamlet was created. The initial construction of Flag Fen and of Must Farm were 400 years apart.

The commonality lies in the evolving adjustments of the local communities to the challenges and opportunities presented by an ever-changing water-edge landscape.

Comparison of Must Farm and Flag Fen (CAU)

The Bronze Age landscape succession through Early Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age and Late Bronze Age, with transition from salt marsh to freshwater fen. Image: CAU

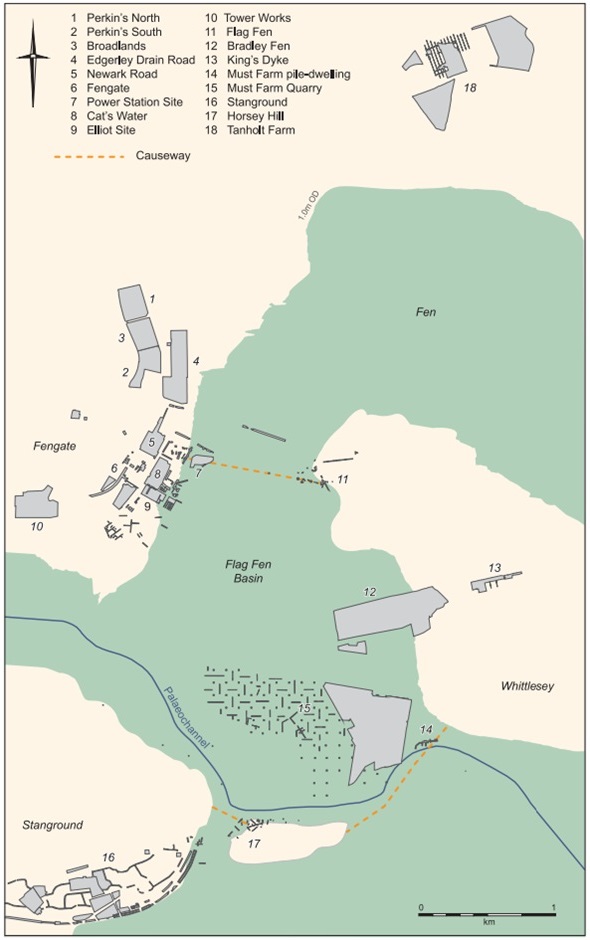

To those interested in Peterborough archaeology it is, of course, not just the links to Flag Fen itself which are important. Many prehistoric sites have been investigated around the Flag Fen basin over the past 60 years. The map below is a useful summary; you can find information about Flag Fen and about Fengate elsewhere on this website.

Sites within the Flag Fen Basin; the 1 m OD contour marks the approximate location of the fen-edge 1000–500 BC. Image: CAU