About Peakirk Archaeological Survey Team – PAST

PAST is a self-funding, independent group, founded in 2013 by Greg Prior, Avril Lumley Prior, Jon Clynch and geophysicist Bob Randall, following two successful ‘digs’ in Peakirk supervised by ex-Time Team presenter, Dr Carenza Lewis, in 2012. Since then, PAST recruited other talented members. Its aims are to discover more about Peakirk’s rich heritage through a variety of sources (including written and landscape evidence), non-invasive geophysical surveys and, where viable, excavations. Findings are always recorded through formal archaeological reports and features in the local magazine, The Village Tribune. Presentations are given at conferences and to interest groups in order to generate an interest and pride in Peakirk’s past and an understanding of how this small settlement fits into the ‘bigger picture’.

About Peakirk

Peakirk is located on the western margins of Borough Fen, formerly in Northamptonshire, now in Cambridgeshire. A village green lies in the medieval heart of the settlement, to the east of St. Pega’s church. The green is bisected by the Roman watercourse, constructed between the River Nene at Peterborough and the River Witham during the first century AD, and known since at least the eleventh century as Car Dyke.

The place-name, Peakirk, meaning ‘Pega’s Church’, a corruption of the Old English Pegechirche, implies that the settlement was renamed by Scandinavian incomers during the late-ninth to early-eleventh centuries. Pega was the daughter of Penwalh (a Mercian nobleman) and sister to St. Guthlac, the hermit of Crowland. By c.714, she reputedly had founded a cell on the site of Peakirk Hermitage (north-east of the green) before embarking upon a pilgrimage to Rome, where she is said to have died in 719. Therefore, we can assume that Peakirk received its name shortly after her departure or death through her association with the place. There is no reference to Peakirk in Domesday Book and it is thought to have been included with the manor of Glinton. St Benedict’s, Glinton, remained a chapel-of-ease to St Pega’s until 1865, when the two communities become separate parishes.

PAST Projects in Peakirk

1. Car Dyke

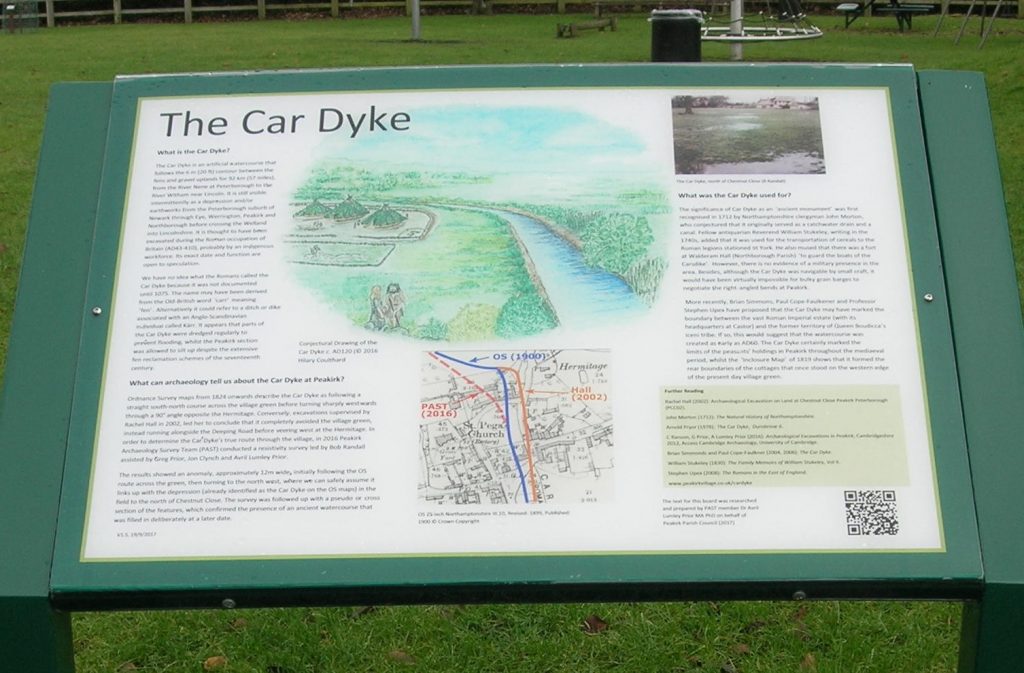

The first major project was in 2016 and involved plotting the course of Car Dyke across the village green, culminating in the erection of an interpretation board funded by Peakirk Parish Council.

Ordnance Survey Maps from 1824 onwards describe Car Dyke as following a straight north-south course across the green before turning sharply westwards through a 90˚ angle opposite Peakirk Hermitage. Conversely, excavations supervised by Rachel Hall, prior to the construction of Chapel Cottage in 2002, led her to conclude that the watercourse completely avoided the green, instead running alongside the Deeping Road before veering westwards at the Hermitage.

In order to determine Car Dyke’s true route, Peakirk Archaeological Survey Team conducted a resistivity survey led by Bob Randall. The results showed an anomaly, approximately 12m wide initially following the OS route across the green, then turning to the north-west, where it links up with the depression (already identified as Car Dyke on the OS Maps) in the field to the north of Chestnut Close. A pseudo- or cross-section of the feature confirmed the presence of an ancient watercourse. This was followed by an ongoing series of test pit excavations across Car Dyke (2016/17; 2019/20). The assemblage of pottery sherds retrieved to date suggests that it was deliberately filled in between the ninth and eleventh centuries, possibly coinciding with the erection of the church in 1014/15.

2. A Romano-British villa?

The 2012 excavations revealed several Romano-British ‘hot-spots’ in Peakirk, all to the west of Car Dyke and mostly in the vicinity of the village green. Moreover, the discovery of an amphora and sherds of high-status pottery in the grounds of the Old Rectory in 1913 and 1919 indicate that there was a significant farmstead or villa nearby. In May 2016, rumours were afoot that its foundations lay beneath the paddock at the end of Bull Lane. Indeed, images from Google Earth showed a series of crop-marks so convincing that they had attracted ‘night-hawks’ [unofficial metal detectorists] whilst the paddock and adjacent house stood empty.

Once the new owners had settled in, PAST obtained permission to conduct a resistivity survey with the possibility of test pitting later. The survey revealed that the section closest to the house yielded the greatest levels of resistance. In 2017, five metre-square test pits were sunk over the supposed ‘villa’ site. Disappointingly, our earliest finds dated from the late-eleventh century. Moreover, the area of high resistance shown on the readings was the hardcore of what was later confirmed to be a mid twentieth-century stack-yard!

3. Chestnut Close Cottages

In 2018, PAST investigated a row of cottages which once abutted the western edge of the village green. They are described on the 1819 ‘Inclosure Map’ but were absent for the Ordnance Survey Map of 1887. After yet another geophysical survey, five test pits were excavated over areas of high resistivity. The finds revealed not one but two main phases of occupation.

Pottery sherds and a late thirteenth-century French jetton offer a rough date for the earliest occupation of the site. This matched a nationwide period of intensive farming needed to feed a rapidly-increasing population, when even the marginal lands of the parish were cultivated and peasants’ crofts and tofts were squeezed into vacant spaces within the ‘village envelope’. Like many agricultural labourers’ homes, the cottages probably were timber-framed, wattle-and-daub structures set on a stone plinth and roofed with reeds, locally-sourced materials that would have either decayed or been recycled. The site appears to have been abandoned by the mid-fourteenth century, perhaps, because the occupants died of plague or moved to ground that was less susceptible to flooding.

The second habitation phase possibly corresponded with the turnpiking of the London-Lincoln post road via Peakirk, in 1792. Building materials unearthed included fragments of brick, Collyweston slate, quarry-tiles and copious pieces of plaster with wattle-and-daub imprints. There was also evidence of a forge (slag, burnt brick and iron nails), which seems to have become derelict after the death of the blacksmith in 1865. An image published in The London Illustrated News concerning the inundation of the Fens, in 1880, shows a chimney of one of the cottages. This enabled us to narrow the demolition date down to between 1880 and c.1886, maybe due to flood damage.

4. Outreach and Community Projects

PAST is committed to working with the local community. In 2019, it launched its St Pega’s Package to help raise money to replace the church roof that was stolen in November 2018. This has proved very popular, with interest groups descending upon Peakirk to be treated to a history of the church, explanation of the fourteenth-century wall-paintings, refreshments provided by the ladies of the parish and a wheelchair-friendly tour of the village, terminating (weather permitting) at an archaeological test-pit.

PAST has been working in conjunction with Peakirk Parish Council too, by planting trees on their behalf along St Pega’s Road, one of the approaches to the village to enhance the environment and vista. PAST members have also donated their own trees, which are now flourishing along the ancient Peakirk/Glinton Footway.