Dating English Houses by External Features

This introductory guide is by FRAG member, Tony Camplin. It is based on a 10 minute presentation made at our September 2021 meeting.

Dating houses is not an exact science; one can for example build a new one in an old style but not of course the other way around. However, in most cases it is surprisingly accurate especially if more than one feature is taken into account. This article is about dating houses, that is places where normal people lived and not palaces, stately homes, castles etc.

There aren’t really any very old houses left here in England now, that’s ones built before the 1200s. Of course, most of the older houses have been substantially altered “modernised” over the years so you have to do a bit, sometimes quite a lot, of detective work to recognise the original parts. Early Norman stone buildings had small rounded windows, later in the 13th century they became pointed but surviving buildings from this period weren’t houses as far as we’re concerned.

Cruck Beam Diagram

Cruck Beam – Upper Floor Only

Early houses used cruck beams at their ends and in the case of the larger ones in between as well. They were relatively low, usually just one storey.

A cruck beam is one piece of timber from the ground to the roof apex. Initially one tree was used per corner, ie four per small house. Towards the end of the 13th century these were split, not sawn, in half so cutting down on the number of trees needed, only two now, and this resulted giving them a more symmetric appearance.

Later still in the 14th century these long beams were done away with. One beam, a straight one now only went up to the roof level and the curved beam was used to form the roof so it was possible to make houses a little taller. This may have been necessary because of a shortage of suitable trees or just an improvement. Huge numbers of trees were used. It has been estimated that a house would have required about 111 trees to build.

Cruck Beam House Examples

Early Timber Framing

The walls of early houses used upright and cross beams that formed squares or rectangles about six feet across. From the 14th century onwards these were replaced by wall and floor plates with vertical uprights connecting them together; there were relatively large gaps between them. Towards the end of the century this studding became much closer together and from the 15th century onwards diagonal bracing timbers, originally curved, were introduced. This greatly improved the strength and rigidly of the walls and that led to “jetted” upper floors.

Diagonal Bracing

Decorative as well as practical, this form of bracing is referred to as “Kentish bracing”.

The braces are paired to provide lateral rigidity across the frame in either direction to help support the upper floor.

Jetted Floor With Diagonal Bracing

These jetted or overlapping upper floor houses became popular from the 16th century often with several floors so that there was quite a pronounced overhang making streets very narrow and the upper floors were very close together in houses either side of a street. The Shambles in York is a good example.

The Shambles, York

About this time square framed windows and doors were introduced; previously, especially doors, had curved tops. Also, they were starting to be put in symmetrically; previously, windows were just put in anywhere and at all sorts of different levels.

Timber Framing With Arch Doorframe

Old Arch Doorway Now Squared Off

Arched Doorway

Wattle And Daub With Pargeting

Walls, particularly the spaces between the timbers were filled in with wattle and daub, cob or something similar. Later plaster was used sometimes covered with patterns often very ornamental; this plaster work is called pargeting.

Decorative Beam Patterns

From the 16th-17th centuries they started to use elaborate patterns of beams that were exposed because they were meant to be seen. Prior to that the construction timbers were covered up with the wall covering, usually plaster.

Common patterns of these decorative beams were herring bone, chevrons, stars and crosses. After the initial flurry this became more restrained and from the late 17th century houses went back to being much more lightly timbered.

Brick Infill

Bricks were introduced from later 15th century onwards but at that time they were very expensive so only used for palaces etc and then only for infills between the timber work. The first bricks came from Flanders, presumably as ships ballast and were 1.5 inches thick. Towards the end of the 15th and early 16th centuries this had changed to 2 inches. However, in 1571 brick sizes were standardised by statue to 2.25 inches. By the end of the 17th century 2.5 inches became the norm and by the end of the 1700s it had increased to 3 inches. To sum up, the smaller the bricks are, the older they are; bricks are a very good indicator of the properties age. Incidentally, nowadays bricks are 2.75 inches thick.

Mullion Barred Windows

Casement Window

Windows with glass in panels first became used generally from the 16th century onwards. Before that, windows had mullion bars either left open or often covered with oiled translucent parchment stretched over them, which obviously haven’t survived. All of the windows had sturdy shutters that could be closed at night or in inclement weather.

Initially glass was only used in large houses in bay windows called oriels. Originally, windows were of the casement type, hinged on the edge and opening like a door. Sometimes two together meeting against an upright in the middle, all that was left of the original mullion bars.

Early Thick Barred Sash Window

Later Georgian Window

In about 1680 sash windows, originally with flat tops and bottoms, set on the outside of the building, started to be used. The first ones had small panes with thick glazing bars, about two inches thick in Queen Anne buildings. Later, in Georgian times, they became very delicate. They were set in openings with slightly curved tops made up of individually shaped bricks or in posh houses, shaped stones. The sills were made of a single piece of stone.

From 1704 the window had to be set back into wall, not on the outside, because of new fire regulations. These were first introduced in London. In the 19th century, Victorian times, larger panes of much lighter glass came into use, sometimes just two per sash. The tops of these sashes were still square but nibs were put into the bottoms to strengthen them. The top of the window openings were squared off and flat stone lintels came into use rather like the sills.

Victorian Nibs

Victorian Sash Windows

In 1697 a lot of windows were bricked up in order to avoid the new tax put on windows. This is a bit confusing though because houses were often built with dummy windows for decorative purposes. In the latter 17th century they started building houses symmetrical with evenly spaced windows and more central doors. In the Georgian period it became fashionable to have taller narrower windows, gutters were being hidden behind parapets or in roof gullies, external cornices half way up the wall, either of brick or stone became popular. Doors had big projecting hoods with fake pillars either side of the front door with arched fanlights above them. Number 10 Downing Street is a perfect example. At this time the houses were built mainly to show off one’s wealth, often quite shoddily.

No 10 Downing Street

Towards the end of the 18th century Welsh slate started to replace thatch. There had always been tiles, even in the Roman period. These slate roofs made it easier to put in dormer windows and consequently loft spaces became servants’ quarters. This was also because with roofs not being so steep there was more room inside them.

Peterborough Museum

Decorative iron balconies came into general use from about 1770 as seen in Bath, or for a more local example take a look at Peterborough Museum.

Chimneys came into use from the 16th century. Originally the fire was in the centre of the big (hall) room this was then moved to one end and baffles were used to divert the smoke to the outside. These “smoke rooms” were then fitted with proper openings that in turn evolved into proper chimneys. In time they developed into inglenooks and a little window was added beside the fire, a little room within a room out of the draughts. From the 18th century onwards two chimneys, one each end, became the norm.

Floorplan of a 17th century Dartmoor Longhouse, shippon to right

Devon Longhouse

From the 1700s spaces that were originally used to accommodate animals (shippons) started to be used as living spaces. Examples are Wealden and Devon longhouses.

Houses continued developing, in the early 1900s there were Edwardian terrace workers houses.

Edwardian Terrace Street

In the 1920s the art deco style and Crittal, metal framed windows were popular.

Council houses came into being from 1919 onwards. Then there were the mock Tudor houses of the 1930s. Suburban Metro-Land for example.

Art Deco Houses

1930’s Mock Tudor

Poster Advertising Metro-Land

These were followed by return windows, ie one window in two or more walls of a room. Big picture windows were a feature of the 1970s. In the 1980s to 1990s legislation came in to make them much smaller in order to conserve heat. After that there were plastic windows and now of course we have solar panels on roofs.

That’s a brief history of the main housing styles over approximately the last thousand years. Apart from dating individual buildings it can be used to chart the growth of towns and see how their centres have changed over the years.

Dating Houses – More Information

Traditional Timber Framing – A Brief Introduction, University of the West of England

Dating of English Houses, Smith and Yates, Field Studies Council, 1968

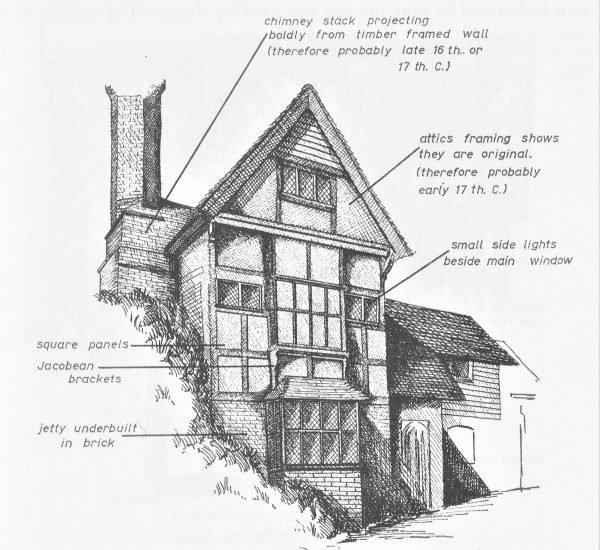

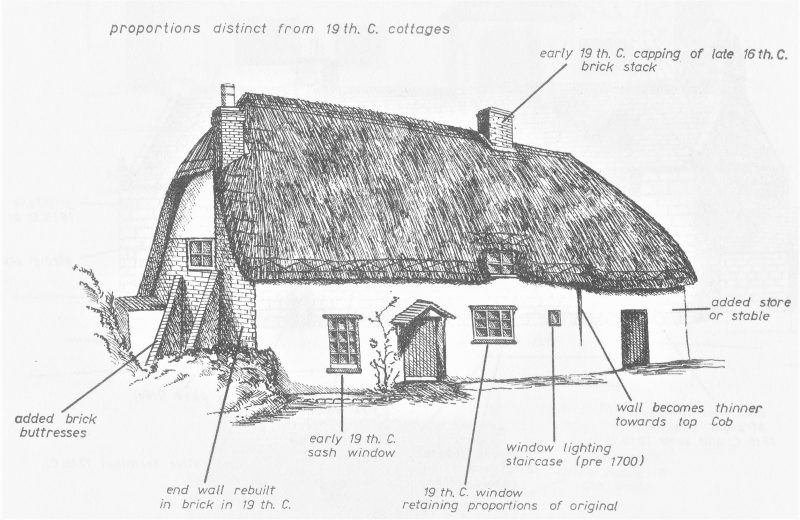

A regularly reprinted paper originally published in the journal, Field Studies. There’s lots of useful detail but particularly accessible are annotated sketches of over 30 real examples. Each helps you spot the clues you need when it comes to dating houses from external evidence.

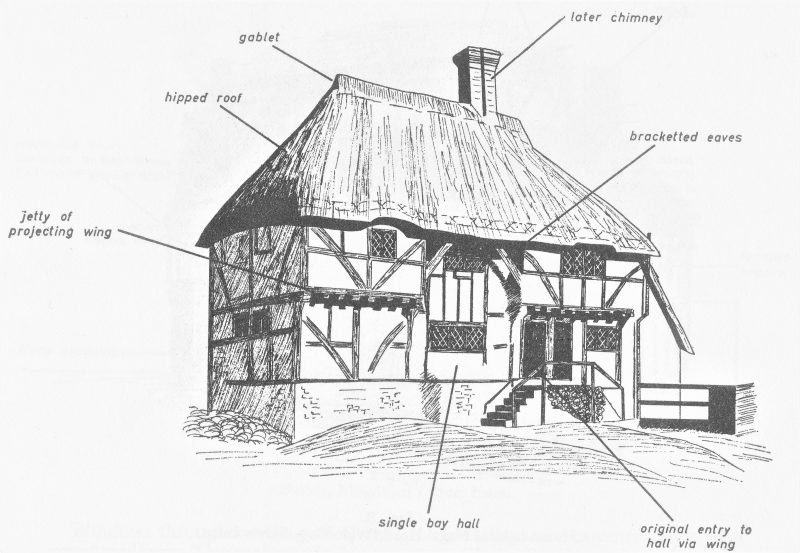

The Old Ship, Bignor, Sussex. Wealden type house (Image Credit – RT Mason)

Penshurst, Kent

Harts Cottage, Corfe Mullen, Dorset

How to Date Buildings, Trevor Yorke, Countryside Books, 2017

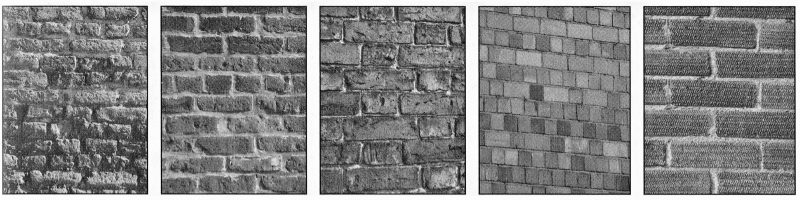

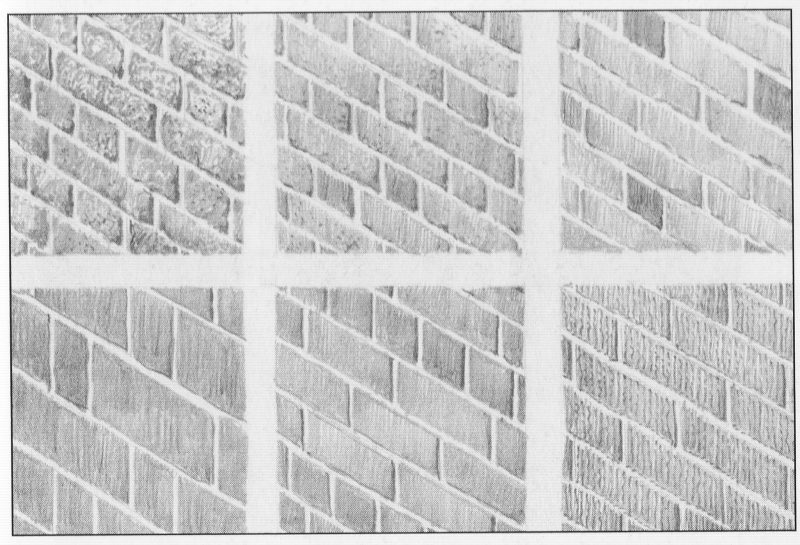

A useful illustrated guide which takes you through the various tell-tale features including chimneys, roofing and doors. This section on bricks is a good example where brick type, bonding and decoration all provide dating evidence for English houses.

The earliest bricks dating from the late Medieval and Tudor period tend to be thin and long, with a rough surface reflecting the clay which would have been extracted close to the building site (left). As brick grew in popularity during the 17th century, so local brickworks became established and the size of brick standardized (centre left). By the early 19th century, bricks were uniform in size (centre), although they were still handmade with their colour and finish depending on the local clay used. A recessed upper and/or lower surface (frog) was introduced from around 1800, although this can only be seen if an individual brick is exposed. From the mid 19th century new methods of mass production, machine cutting, and improved transport meant finer quality, sharp edged bricks were widely available (centre right). Pressed patterns in the face of bricks were popular from the 1930s (right).

Bonding is the way in which bricks are laid in the wall and the pattern formed on the outside from the long sides of the bricks (stretchers) and the short ends (headers). Early brick walls usually have no clear pattern. English bond is a row of headers, then one of stretchers (top left) and was developed in the 16th century. Flemish bond has a header followed by a stretcher in each course (top centre), and became standard from the early 18th through to the mid 19th centuries. Both of these could have a number of courses of stretchers inserted so less bricks were used, referred to as a garden bond (top right). Brick tax (1784-1850), which was applied on the quantity used, encouraged manufacturers to make bricks larger and some builders to use rat bond, with the bricks stacked up on their thinner sides (bottom left). English bond was reintroduced in the late 19th century, often in its garden bond version (bottom centre). Stretcher bond, with a cavity between the inner and outer face (bottom right), can be found in the late 19th century and became standard from the 1920s.

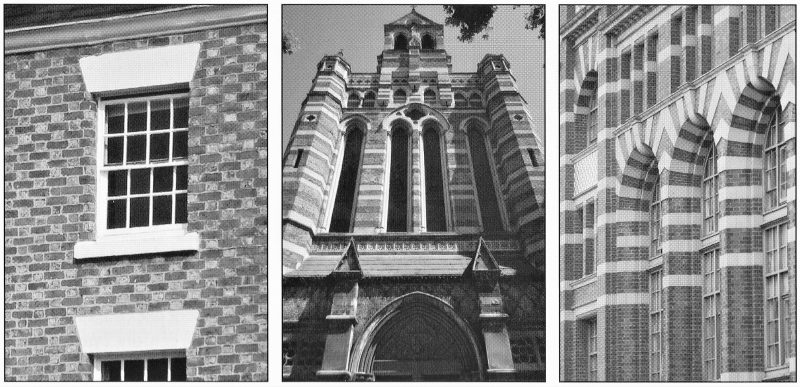

Diamond shaped patterns formed in darker bricks were popular in the 15th and 16th centuries and were re-introduced in many Victorian buildings. Regency brickwork often had chequered patterns formed from red mixed with cream or grey bricks (left). Polychromatic patterns and stripes formed by using red, cream and black bricks are distinctive of the mid 1850s to late 1870s (centre). More restrained bands of red brick and cream stone (right) were fashionable in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.